Douay–Rheims Bible

| Douay–Rheims Bible | |

|---|---|

Title page of the Old Testament, Tome 1 (1609) | |

| Full name | Douay Rheims Bible |

| Abbreviation | DRB |

| Language | Early Modern English |

| OT published | 1609–1610 |

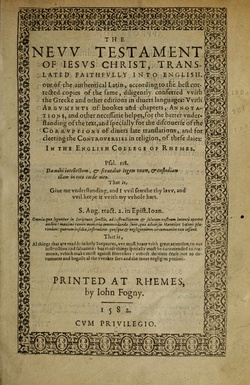

| NT published | 1582 |

| Authorship | English College at Rheims and Douay |

| Derived from | Latin Vulgate |

| Textual basis |

|

| Translation type | Formal equivalence translation of the Vulgate compared with Hebrew and Greek sources for accuracy. The 1582 version used the Leuven Vulgate. The Challoner revision used the Clementine Vulgate. |

| Reading level | University Academic, Grade 12 |

| Version | Revised in 1749, 1750, and 1752 by Richard Challoner (DRC) |

| Copyright | Public domain |

| Religious affiliation | Catholic Church |

In the beginning God created heaven, and earth. And the earth was void and empty, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the spirit of God moved over the waters. And God said: Be light made. And light was made.

For God so loved the world, as to give his only begotten Son; that whosoever believeth in him, may not perish, but may have life everlasting. | |

The Douay–Rheims Bible (/ˌduːeɪ ˈriːmz, ˌdaʊeɪ -/,[1] US also /duːˌeɪ -/), also known as the Douay–Rheims Version, Rheims–Douai Bible or Douai Bible, and abbreviated as D–R, DRB, and DRV, is a translation of the Bible from the Latin Vulgate into English made by members of the English College, Douai, in the service of the Catholic Church.[2] The New Testament portion was published in Reims, France, in 1582, in one volume with extensive commentary and notes. The Old Testament portion was published in two volumes twenty-seven years later in 1609 and 1610 by the University of Douai. The first volume, covering Genesis to Job, was published in 1609; the second, covering the Book of Psalms to 2 Maccabees (spelt "Machabees") plus the three apocryphal books of the Vulgate appendix following the Old Testament (Prayer of Manasseh, 3 Esdras, and 4 Esdras), was published in 1610. Marginal notes took up the bulk of the volumes and offered insights on issues of translation, and on the Hebrew and Greek source texts of the Vulgate.

The purpose of the version, both the text and notes, was to uphold Catholic tradition in the face of the Protestant Reformation which up until the time of its publication had dominated Elizabethan religion and academic debate. As such it was an effort by English Catholics to support the Counter-Reformation. The New Testament was reprinted in 1600, 1621 and 1633. The Old Testament volumes were reprinted in 1635 but neither thereafter for another hundred years. In 1589, William Fulke collated the complete Rheims text and notes in parallel columns with those of the Bishops' Bible. This work sold widely in England, being re-issued in three further editions to 1633. It was predominantly through Fulke's editions that the Rheims New Testament came to exercise a significant influence on the development of 17th-century English.[3]

Much of the first edition employed a densely Latinate vocabulary, making it extremely difficult to read the text in places. Consequently, this translation was replaced by a revision undertaken by Bishop Richard Challoner; the New Testament in three editions of 1749, 1750, and 1752; the Old Testament (minus the Vulgate apocrypha), in 1750. Subsequent editions of the Challoner revision, of which there have been very many, reproduce his Old Testament of 1750 with very few changes. Challoner's New Testament was, however, extensively revised by Bernard MacMahon in a series of Dublin editions from 1783 to 1810. These Dublin versions are the source of some Challoner bibles printed in the United States in the 19th century. Subsequent editions of the Challoner Bible printed in England most often follow Challoner's earlier New Testament texts of 1749 and 1750, as do most 20th-century printings and online versions of the Douay–Rheims bible circulating on the internet.

Although the Jerusalem Bible, New American Bible Revised Edition, Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition, and New Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition are the most commonly used Bibles in English-speaking Catholic churches, the Challoner revision of the Douay–Rheims often remains the Bible of choice of more traditional English-speaking Catholics.[4]

Origin

[edit]

Following the English Reformation, some Catholics went in exile to the European mainland. The centre of English Catholicism was the English College at Douai (University of Douai, France) founded in 1568 by William Allen, formerly of Queen's College, Oxford, and Canon of York, and subsequently cardinal, for the purpose of training priests to convert the English again to Catholicism. And it was here where the Catholic translation of the Bible into English was produced.

A run of a few hundred or more of the New Testament, in quarto form (not large folio), was published in the last months of 1582 (Herbert #177), during a temporary migration of the college to Rheims; consequently, it has been commonly known as the Rheims New Testament. Though he died in the same year as its publication, this translation was principally the work of Gregory Martin, formerly Fellow of St. John's College, Oxford, close friend of Edmund Campion. He was assisted by others at Douai, notably Allen, Richard Bristow, William Reynolds and Thomas Worthington,[5][6] who proofed and provided notes and annotations. The Old Testament is stated to have been ready at the same time but, for want of funds, it could not be printed until later, after the college had returned to Douai. It is commonly known as the Douay Old Testament. It was issued as two quarto volumes dated 1609 and 1610 (Herbert #300). These first New Testament and Old Testament editions followed the Geneva Bible not only in their quarto format but also in the use of Roman type.[citation needed]

As a recent translation, the Rheims New Testament had an influence on the translators of the King James Version. Afterwards it ceased to be of interest to the Anglican church. Although the cities are now commonly spelled as Douai and as Reims, the Bible continues to be published as the Douay–Rheims Bible and has formed the basis of some later Catholic Bibles in English.

The title page runs: "The Holy Bible, faithfully translated into English out of the authentic Latin. Diligently conferred with the Hebrew, Greek and other Editions". The cause of the delay was "our poor state of banishment", but there was also the matter of reconciling the Latin to the other editions. William Allen went to Rome and worked, with others, on the revision of the Vulgate. The Sixtine Vulgate edition was published in 1590. The definitive Clementine text followed in 1592. Worthington, responsible for many of the annotations for the 1609 and 1610 volumes, states in the preface: "we have again conferred this English translation and conformed it to the most perfect Latin Edition."[7]

Style

[edit]The Douay–Rheims Bible is a translation of the Latin Vulgate, which is itself a translation of Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek texts. The Vulgate was largely created due to the efforts of Saint Jerome (345–420), whose translation was declared to be the authentic Latin version of the Bible by the Council of Trent. While the Catholic scholars "conferred" with the Hebrew and Greek originals, as well as with "other editions in diverse languages",[8] their avowed purpose was to translate after a strongly literal manner from the Latin Vulgate, for reasons of accuracy as stated in their Preface and which tended to produce, in places, stilted syntax and Latinisms. The following short passage (Ephesians 3:6–12), is a fair example, admittedly without updating the spelling conventions then in use:

The Gentiles to be coheires and concorporat and comparticipant of his promise in Christ JESUS by the Gospel: whereof I am made a minister according to the gift of the grace of God, which is given me according to the operation of his power. To me the least of al the sainctes is given this grace, among the Gentils to evangelize the unsearcheable riches of Christ, and to illuminate al men what is the dispensation of the sacrament hidden from worldes in God, who created all things: that the manifold wisdom of God, may be notified to the Princes and Potestats in the celestials by the Church, according to the prefinition of worldes, which he made in Christ JESUS our Lord. In whom we have affiance and accesse in confidence, by the faith of him.

Other than when rendering the particular readings of the Vulgate Latin, the English wording of the Rheims New Testament follows more or less closely the Protestant version first produced by William Tyndale in 1525, an important source for the Rheims translators having been identified as that of the revision of Tyndale found in an English and Latin diglot New Testament, published by Miles Coverdale in Paris in 1538.[9][10][11] Furthermore, the translators are especially accurate in their rendition of the definite article from Greek to English, and in their recognition of subtle distinctions of the Greek past tense, neither of which is capable of being represented in Latin. Consequently, the Rheims New Testament is much less of a new version, and owes rather more to the original languages, than the translators admit in their preface. Where the Rheims translators depart from the Coverdale text, they frequently adopt readings found in the Protestant Geneva Bible[12] or those of the Wycliffe Bible, as this latter version had been translated from the Vulgate, and had been widely used by English Catholic churchmen unaware of its Lollard origins.[13][14]

Nevertheless, it was a translation of a translation of the Bible. Many highly regarded translations of the Bible routinely consult Vulgate readings, especially in certain difficult Old Testament passages; but nearly all modern Bible versions, Protestant and Catholic, go directly to original-language Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek biblical texts as their translation base, and not to a secondary version like the Vulgate. The translators justified their preference for the Vulgate in their Preface, pointing to accumulated corruptions within the original language manuscripts available in that era, and asserting that Jerome would have had access to better manuscripts in the original tongues that had not survived. Moreover, they could point to the Council of Trent's decree that the Vulgate was, for Catholics, free of doctrinal error.

In their decision consistently to apply Latinate language, rather than everyday English, to render religious terminology, the Rheims–Douay translators continued a tradition established by Thomas More and Stephen Gardiner in their criticisms of the biblical translations of William Tyndale. Gardiner indeed had himself applied these principles in 1535 to produce a heavily revised version, which has not survived, of Tyndale's translations of the Gospels of Luke and John. More and Gardiner had argued that Latin terms were more precise in meaning than their English equivalents, and consequently should be retained in Englished form to avoid ambiguity. However, David Norton observes that the Rheims–Douay version extends the principle much further. In the preface to the Rheims New Testament the translators criticise the Geneva Bible for their policy of striving always for clear and unambiguous readings; the Rheims translators proposed rather a rendering of the English biblical text that is faithful to the Latin text, whether or not such a word-for-word translation results in hard to understand English, or transmits ambiguity from the Latin phrasings:

we presume not in hard places to modifie the speaches or phrases, but religiously keepe them word for word, and point for point, for feare of missing or restraining the sense of the holy Ghost to our phantasie...acknowledging with S. Hierom, that in other writings it is ynough to give in translation, sense for sense, but that in Scriptures, lest we misse the sense, we must keep the very wordes.

This adds to More and Gardiner the opposite argument, that previous versions in standard English had improperly imputed clear meanings for obscure passages in the Greek source text where the Latin Vulgate had often tended to rather render the Greek literally, even to the extent of generating improper Latin constructions. In effect, the Rheims translators argue that, where the source text is ambiguous or obscure, then a faithful English translation should also be ambiguous or obscure, with the options for understanding the text discussed in a marginal note:

so, that people must read them with licence of their spiritual superior, as in former times they were in like sort limited. such also of the Laitie, yea & of the meaner learned Clergie, as were permitted to read holie Scriptures, did not presume to inteprete hard places, nor high Mysteries, much lesse to dispute and contend, but leaving the discussion thereof to the more learned, searched rather and noted the godlie and imitable examples of good life and so learned more humilitie, obedience...

The translation was prepared with a definite polemical purpose in opposition to Protestant translations (which also had polemical motives). Prior to the Douay-Rheims, the only printed English language Bibles available had been Protestant translations. The Tridentine–Florentine Biblical canon was naturally used, with the Deuterocanonical books incorporated into the Douay–Rheims Old Testament, and only 3 Esdras, 4 Esdras and the Prayer of Manasses in the Apocrypha section.

The translators excluded the apocryphal Psalm 151, this unusual oversight given the otherwise "complete" nature of the book is explained in passing by the annotations to Psalm 150 that "S. Augustin in the conclusion of his ... Sermons upon the Psalms, explicateth a mysterie in the number of an hundred and fieftie[.]"

Influence

[edit]

In England the Protestant William Fulke unintentionally popularized the Rheims New Testament through his collation of the Rheims text and annotations in parallel columns alongside the 1572 Protestant Bishops' Bible. Fulke's original intention through his first combined edition of the Rheims New Testament with the so-called Bishops' Bible was to prove that the Catholic-inspired text was inferior to the Protestant-influenced Bishops' Bible, then the official Bible of the Church of England. Fulke's work was first published in 1589; and as a consequence the Rheims text and notes became easily available without fear of criminal sanctions.

The translators of the Rheims appended a list of these unfamiliar words;[15] examples include "acquisition", "adulterate", "advent", "allegory", "verity", "calumniate", "character", "cooperate", "prescience", "resuscitate", "victim", and "evangelise". In addition the editors chose to transliterate rather than translate a number of technical Greek or Hebrew terms, such as "azymes" for unleavened bread, and "pasch" for Passover.

Challoner Revision

[edit]Translation

[edit]The original Douay–Rheims Bible was published during a time when Catholics were being persecuted in Britain and Ireland and possession of the Douay–Rheims Bible was a crime. By the time possession was not a crime the English of the Douay–Rheims Bible was a hundred years out-of-date. It was thus substantially "revised" between 1749 and 1777 by Richard Challoner, the Vicar Apostolic of London. Bishop Challoner was assisted by Father Francis Blyth, a Carmelite Friar. Challoner's revisions borrowed heavily from the King James Version (being a convert from Protestantism to Catholicism and thus familiar with its style). The use of the Rheims New Testament by the translators of the King James Version is discussed below. Challoner not only addressed the odd prose and much of the Latinisms, but produced a version which, while still called the Douay–Rheims, was little like it, notably removing most of the lengthy annotations and marginal notes of the original translators, the lectionary table of gospel and epistle readings for the Mass. He retained the full 73 books of the Vulgate proper, aside from Psalm 151. At the same time he aimed for improved readability and comprehensibility, rephrasing obscure and obsolete terms and constructions and, in the process, consistently removing ambiguities of meaning that the original Rheims–Douay version had intentionally striven to retain.

This is Ephesians 3:6–12 in the original 1582 Douay-Rheims New Testament:

The Gentils to be coheires and concorporate and comparticipant of his promise in Christ IESVS by the Ghospel: wherof I am made a Minister according to the guift of the grace of God, which is giuen me according to the operation of his power. To me the least of al the Saints is giuen this grace, among the Gentils to euangelize the vnsearcheable riches of Christ, & to illuminate al men what is the dispensation of the sacrament hidden from worlds in God, who created al things: that the manifold wisedom of God, may be notified to the Princes & Potestates in the Celestials by the Church, according to the prefinition of worlds, which he made in Christ IESVS our Lord. In whom we haue affiance and accesse in confidence by the faith of him.

The same passage in Challoner's revision gives a hint of the thorough stylistic editing he did of the text:

That the Gentiles should be fellow heirs and of the same body: and copartners of his promise in Christ Jesus, by the gospel, of which I am made a minister, according to the gift of the grace of God, which is given to me according to the operation of his power. To me, the least of all the saints, is given this grace, to preach among the Gentiles the unsearchable riches of Christ: and to enlighten all men, that they may see what is the dispensation of the mystery which hath been hidden from eternity in God who created all things: that the manifold wisdom of God may be made known to the principalities and powers in heavenly places through the church, according to the eternal purpose which he made in Christ Jesus our Lord: in whom we have boldness and access with confidence by the faith of him.

For comparison, the same passage of Ephesians in the King James Version and the 1534 Tyndale Version, which influenced the King James Version:

That the Gentiles should be fellow heirs, and of the same body, and partakers of his promise in Christ by the gospel: whereof I was made a minister, according to the gift of the grace of God given unto me by the effectual working of his power. Unto me, who am less than the least of all saints, is this grace given, that I should preach among the Gentiles the unsearchable riches of Christ; and to make all men see what is the fellowship of the mystery, which from the beginning of the world hath been hid in God, who created all things by Jesus Christ: to the intent that now unto the principalities and powers in heavenly places might be known by the church the manifold wisdom of God, according to the eternal purpose which he purposed in Christ Jesus our Lord: in whom we have boldness and access with confidence by the faith of him.

— KJV

That the gentiles should be inheritors also, and of the same body, and partakers of his promise that is in Christ, by the means of the gospel, whereof I am made a minister, by the gift of the grace of God given unto me, through the working of his power. Unto me the least of all saints is this grace given, that I should preach among the gentiles the unsearchable riches of Christ, and to make all men see what the fellowship of the mystery is which from the beginning of the world hath been hid in God which made all things through Jesus Christ, to the intent, that now unto the rulers and powers in heaven might be known by the congregation the manifold wisdom of God, according to that eternal purpose, which he purposed in Christ Jesu our Lord, by whom we are bold to draw near in that trust, which we have by faith on him.

— Tyndale

Publication

[edit]

Challoner issued a New Testament edition in 1749. He followed this with an edition of the whole bible in 1750, making some 200 further changes to the New Testament. He issued a further version of the New Testament in 1752, which differed in about 2,000 readings from the 1750 edition, and which remained the base text for further editions of the bible in Challoner's lifetime. In all three editions the extensive notes and commentary of the 1582/1610 original were drastically reduced, resulting in a compact one-volume edition of the Bible, which contributed greatly to its popularity. Gone also was the longer paragraph formatting of the text; instead, the text was broken up so that each verse was its own paragraph. The three apocrypha, which had been placed in an appendix to the second volume of the Old Testament, were dropped. Subsequent editions of the Challoner revision, of which there have been very many, reproduce his Old Testament of 1750 with very few changes.[citation needed]

Challoner's 1752 New Testament was extensively further revised by Bernard MacMahon in a series of Dublin editions from 1783 to 1810, for the most part adjusting the text away from agreement with that of the King James Version, and these various Dublin versions are the source of many, but not all, Challoner versions printed in the United States in the 19th century. Editions of the Challoner Bible printed in England sometimes follow one or another of the revised Dublin New Testament texts, but more often tend to follow Challoner's earlier editions of 1749 and 1750 (as do most 20th-century printings, and on-line versions of the Douay–Rheims bible circulating on the internet). An edition of the Challoner-MacMahon revision with commentary by George Leo Haydock and Benedict Rayment was completed in 1814, and a reprint of Haydock by F. C. Husenbeth in 1850 was approved by Bishop Wareing. A reprint of an approved 1859 edition with Haydock's unabridged notes was published in 2014 by Loreto Publications.

The Challoner version, officially approved by the Church, remained the Bible of the majority of English-speaking Catholics well into the 20th century. It was first published in America in 1790 by Mathew Carey of Philadelphia. Several American editions followed in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, prominent among them an edition published in 1899 by the John Murphy Company of Baltimore, with the imprimatur of James Cardinal Gibbons, Archbishop of Baltimore. This edition included a chronology that was consistent with young-earth creationism (specifically, one based on James Ussher's calculation of the year of creation as 4004 BC). In 1914, the John Murphy Company published a new edition with a modified chronology consistent with new findings in Catholic scholarship; in this edition, no attempt was made to attach precise dates to the events of the first eleven chapters of Genesis, and many of the dates calculated in the 1899 edition were wholly revised. This edition received the approval of John Cardinal Farley and William Cardinal O'Connell and was subsequently reprinted, with new type, by P. J. Kenedy & Sons. Yet another edition was published in the United States by the Douay Bible House in 1941 with the imprimatur of Francis Cardinal Spellman, Archbishop of New York. In 1941 the New Testament and Psalms of the Douay–Rheims Bible were again heavily revised to produce the New Testament (and in some editions, the Psalms) of the Confraternity Bible. However, so extensive were these changes that it was no longer identified as the Douay–Rheims.

In the wake of the 1943 promulgation of Pope Pius XII's encyclical Divino afflante Spiritu, which authorized the creation of vernacular translations of the Catholic Bible based upon the original Hebrew and Greek, the Douay-Rheims/Challoner Bible was supplanted by subsequent Catholic English translations. The Challoner revision ultimately fell out of print by the late 1960s, only coming back into circulation when TAN Books reprinted the 1899 Murphy edition in 1971.[16]

Names of books

[edit]The names, numbers, and chapters of the Douay–Rheims Bible and the Challoner revision follow that of the Vulgate and therefore differ from those of the King James Version and its modern successors, making direct comparison of versions tricky in some places. For instance, the books called Ezra and Nehemiah in the King James Version are called 1 and 2 Esdras in the Douay–Rheims Bible. The books called 1 and 2 Esdras in the King James Version are called 3 and 4 Esdras in the Douay, and were classed as apocrypha. A table illustrating the differences can be found here.

The names, numbers, and order of the books in the Douay–Rheims Bible follow those of the Vulgate except that the three apocryphal books are placed after the Old Testament in the Douay–Rheims Bible; in the Clementine Vulgate they come after the New Testament. These three apocrypha are omitted entirely in the Challoner revision.

The Psalms of the Douay–Rheims Bible follow the numbering of the Vulgate and the Septuagint, whereas those in the KJV follow that of Masoretic Text. For details of the differences see the article on the Psalms. A summary list is shown below:

| Douay–Rheims | King James Version |

|---|---|

| 1–8 | |

| 9 | 9–10 |

| 10–112 | 11–113 |

| 113 | 114–115 |

| 114–115 | 116 |

| 116–145 | 117–146 |

| 146–147 | 147 |

| 148–150 | |

Influence on the King James Version

[edit]The Old Testament "Douay" translation of the Latin Vulgate arrived too late on the scene to have played any part in influencing the King James Version.[17] The Rheims New Testament had, however, been available for over twenty years. In the form of William Fulke's parallel version, it was readily accessible. Nevertheless, the official instructions to the King James Version translators omitted the Rheims version from the list of previous English translations that should be consulted, probably deliberately.

The degree to which the King James Version drew on the Rheims version has, therefore, been the subject of considerable debate; with James G Carleton in his book The Part of Rheims in the Making of the English Bible[18] arguing for a very extensive influence, while Charles C Butterworth proposed that the actual influence was small, relative to those of the Bishops' Bible and the Geneva Bible.

Much of this debate was resolved in 1969, when Ward Allen published a partial transcript of the minutes made by John Bois of the proceedings of the General Committee of Review for the King James Version (i.e., the supervisory committee which met in 1610 to review the work of each of the separate translation 'companies'). Bois records the policy of the review committee in relation to a discussion of 1 Peter 1:7 "we have not thought the indefinite sense ought to be defined"; which reflects the strictures expressed by the Rheims translators against concealing ambiguities in the original text. Allen shows that in several places, notably in the reading "manner of time" at Revelation 13:8, the reviewers incorporated a reading from the Rheims text specifically in accordance with this principle. More usually, however, the King James Version handles obscurity in the source text by supplementing their preferred clear English formulation with a literal translation as a marginal note. Bois shows that many of these marginal translations are derived, more or less modified, from the text or notes of the Rheims New Testament; indeed Rheims is explicitly stated as the source for the marginal reading at Colossians 2:18.

In 1995, Ward Allen in collaboration with Edward Jacobs further published a collation, for the four Gospels, of the marginal amendments made to a copy of the Bishops' Bible (now conserved in the Bodleian Library), which transpired to be the formal record of the textual changes being proposed by several of the companies of King James Version translators. They found around a quarter of the proposed amendments to be original to the translators; but that three-quarters had been taken over from other English versions. Overall, about one-fourth of the proposed amendments adopted the text of the Rheims New Testament. "And the debts of the [KJV] translators to earlier English Bibles are substantial. The translators, for example, in revising the text of the synoptic Gospels in the Bishops' Bible, owe about one-fourth of their revisions, each, to the Geneva and Rheims New Testaments. Another fourth of their work can be traced to the work of Tyndale and Coverdale. And the final fourth of their revisions is original to the translators themselves".[19]

Otherwise the English text of the King James New Testament can often be demonstrated as adopting latinate terminology also found in the Rheims version of the same text. In the majority of cases, these Latinisms could also have been derived directly from the versions of Miles Coverdale or the Wyclif Bible (i.e., the source texts for the Rheims translators), but they would have been most readily accessible to the King James translators in Fulke's parallel editions. This also explains the incorporation into the King James Version from the Rheims New Testament of a number of striking English phrases, such as "publish and blaze abroad" at Mark 1:45.

Douay-Rheims Only movement

[edit]Much like the case with the King James Version, the Douay–Rheims has a number of devotees who believe that it is a superiorly authentic translation in the English language, or, more broadly, that the Douay is to be preferred over all other English translations of Scripture. Apologist Jimmy Akin opposes this view, arguing that while the Douay is an important translation in Catholic history, it is not to be elevated to such status, as new manuscript discoveries and scholarship have challenged that view.[20]

Modern Harvard-Dumbarton Oaks Vulgate

[edit]Harvard University Press, and Swift Edgar and Angela Kinney at Dumbarton Oaks Library have used a version of Challoner's Douay–Rheims Bible as both the basis for the English text in a dual Latin-English Bible (The Vulgate Bible, six volumes) and, unusually, they have also used the English text of the Douay-Rheims in combination with the modern Biblia Sacra Vulgata to reconstruct (in part) the pre-Clementine Vulgate that was the basis for the Douay-Rheims for the Latin text. This is possible only because the Douay-Rheims, alone among English Bibles, and even in the Challoner revision, attempted a word-for-word translation of the underlying Vulgate. A noted example of the literalness of the translation is the differing versions of the Lord's Prayer, which has two versions in the Douay-Rheims: the Luke version uses 'daily bread' (translating the Vulgate quotidianum) and the version in Matthew reads "supersubstantial bread" (translating from the Vulgate supersubstantialem). Every other English Bible translation uses "daily" in both places; the underlying Greek word is the same in both places, and Jerome translated the word in two different ways because then, as now, the actual meaning of the Greek word epiousion was unclear.

The Harvard–Dumbarton Oaks editors have been criticized in the Medieval Review for being "idiosyncratic" in their approach; their decision to use Challoner's 18th-century revision of the Douay-Rheims, especially in places where it imitates the King James Version, rather than producing a fresh translation into contemporary English from the Latin, despite the Challoner edition being "not relevant to the Middle Ages"; and the "artificial" nature of their Latin text which "is neither a medieval text nor a critical edition of one."[21][22]

See also

[edit]- Tyndale Bible (1526)

- Coverdale Bible (1535)

- Matthew Bible (1537)

- Taverner's Bible (1539)

- Great Bible (1539)

- Geneva Bible (1560)

- Bishops' Bible (1568)

- King James Bible (1611)

Citations

[edit]- ^ J. B. Sykes, ed. (1978). "Douai". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English (Sixth edition 1976, Sixth impression 1978 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 309.

- ^ Pope, Hugh. "The Origin of the Douay Bible", The Dublin Review, Vol. CXLVII, N°. 294-295, July/October, 1910.

- ^ Reid, G. J. "The Evolution of Our English Bible", The American Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. XXX, 1905.

- ^ "Douay-Rheims Bible by Baronius Press". www.marianland.com. Retrieved 2019-02-07.

- ^ Gutenberg website

- ^ Original Douay Rheims.com website

- ^ Bernard Orchard, A Catholic Commentary on Holy Scripture, (Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1951). Page 36.

- ^ 1582 Rheims New Testament, "Preface to the Reader."

- ^ Reid, G. J. "The Evolution of Our English Bible", The American Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. XXX, page 581, 1905.

- ^ Bobrick, Benson (2001). The Making of the English Bible. Phoenix. p. 196.

- ^ Dockery, J.B (1969). The English Versions of the Bible; in R.C. Fuller ed. 'A New Catholic Commentary on Holy Scripture'. Nelson. p. 49.

- ^ Bobrick, Benson (2001). The Making of the English Bible. Phoenix. p. 195.

- ^ Bruce, Frederick Fyvie (April 1998), "John Wycliffe and the English Bible" (PDF), Churchman, Church society, archived from the original (PDF) on July 28, 2013, retrieved September 22, 2015

- ^ Dockery, J.B (1969). The English Versions of the Bible; in R.C. Fuller ed. 'A New Catholic Commentary on Holy Scripture'. Nelson. p. 49.

- ^ Appendices, "The Explication of Certaine Wordes" or "Hard Wordes Explicated"

- ^ "About TAN Books and publishers, Inc". tanbooks.com. TAN Books. Archived from the original on December 6, 1998. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ As noted in Pollard, Dr Alfred W. Records of the English Bible: The Documents Relating to the Translation and Publication of the Bible in English, 1525–1611, London, Oxford University Press, 1911.

- ^ Clarendon Press, Oxford 1902

- ^ Allen, Ward S (1995). The Coming of the King James Gospels; a collation of the Translators work-in-progress. University of Arkansas Press. p. 29.

- ^ Akin, Jimmy (February 1, 2002). "Uncomfortable Facts About the Douay-Rheims". Catholic Answers Magazine. Archived from the original on March 24, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ Marsden, Richard (June 26, 2011). "Edgar, The Vulgate Bible vol. 1". The Medieval Review. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ Bruce, Scott G. (February 27, 2012). "Edgar, The Vulgate Bible, Vol. II". The Medieval Review. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

General references

[edit]- Much of the above text was taken from the article "English Versions" by Sir Frederic G. Kenyon in the Dictionary of the Bible edited by James Hastings (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1909).

- "English Translations of the Bible", The Catholic World, Vol. XII, October 1870/March 1871.

- Hugh Pope. English Versions of the Bible, B. Herder Book Co., 1952.

- A. S. Herbert, Historical Catalogue of Printed Editions of the English Bible 1525–1961, London: British and Foreign Bible Society; New York: American Bible Society, 1968. SBN 564-00130-9.

External links

[edit]- Online and print editions of the 16th/17th century Douay–Rheims Bible:

- Complete Douay–Rheims Bible: Complete Douay-Rheims Bible (a scan of the 1635 reprint, Old and New Testaments); Douay-Rheims 1582 and 1610 Online (this site offers the text in easily navigable HTML, but is currently incomplete)

- Facsimile Rheims New Testament of 1582: Google Books; facsimile from Gallica; 1872 edition in parallel with Vulgate

- Facsimile Douay Old Testament of 1609/1610, as reprinted in 1635: Vol. I Vol. II

- Online text of the Challoner revision:

- The Bible, Douay-Rheims, Complete at Project Gutenberg, including EPUB and Kindle editions

- Douay-Rheims (Challoner rev.), fully searchable, including all references and possible to compare with both the Latin Vulgate and Knox Bibles side by side.

- Douay-Rheims (Challoner rev.), searchable, with tabs to switch between DR, DR+LV, and Latin Vulgate

- Douay-Rheims (Challoner rev.) as plain text files (OT ZIP, NT ZIP)

- Douay-Rheims (Challoner rev.), with definitions of unfamiliar words, and searchable via concordance.

- Douay-Rheims (Challoner rev.) as HTML files

- The Douay-Rheims, 1914 John Murphy edition at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Douay–Rheims Bible at the Internet Archive

- Works by Douay–Rheims Bible at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- The History of the Text of the Rheims and Douay Version of Holy Scripture (1859), by John Henry Newman

- History of the Douay Bible and Online Text

- History of the Douay Bible Archived 2015-11-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Title Pages of Early Editions